The Massachusetts Medievalist has been on something of a hiatus, eating blueberries and corn and lobster, visiting Crane’s beach and Walden pond, following on Twitter the revelations at #ISAS2017 (more on that in a future post). But I’ve also been reading a lot of poetry, taking some summer time to read Tracy K. Smith (our new U.S. poet laureate), David Elliott (a Lesley colleague), and Melissa Range. These poems have provided me a mental and emotional break from medieval-studies-as-usual.

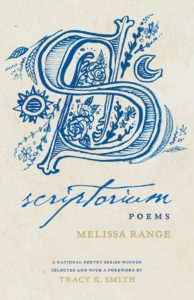

Range’s work is actually not a complete break from medieval-studies-as-usual, however. Her title – Scriptorium – invokes the medieval space in which manuscripts were made, and her work draws on medieval poetry, especially in Old English. She combines medieval theology with contemporary Appalachian culture; she engages with medieval and modern theologians as she questions the world around us, its beauty and its horror, hearkening to Beowulf, Eliot, and Hopkins in a variety of tightly presented forms. In many ways, I am Range’s ideal reader – I know the references to The Dream of the Rood and the Ashburnham House fire without having to check the notes in the back of the book. I am also in awe of the way she uses language and imagery in ways both medieval and completely new: she lets us see “the sailor’s compass / made of ice-trussed stars” (“Ultramarine”). Does “ice-trussed” qualify as an Old English kenning? Maybe, but does it matter?

I was most struck by Range’s series of sonnets interspersed throughout the collection, all named after materials used in manuscript illumination:

Verdigris

Orpiment

Kermes red

Tyrian Purple

Lampblack

Minium

Woad

Ultramarine

Gold leaf

Shell white

All of these sonnets challenge our understanding of the form, even as they adhere to it. “Woad,” for example, contains rap echoes in its internal rhymes, even as it uses half-rhymes to complete its rhyme scheme. It begins:

Once thought lapis on the carpet page, mined

from an Afghani cave, this new-bruise clot

in the monk’s ink pot grew from Boudicca’s plot –

a naturalized weed from a box of black seeds found

with a blue dress in a burial mound.

This collection take us through the medieval world of book- and poetry-making, invoking the calves whose skins will make the manuscript folios (“Scriptorium,” the penultimate poem in the collection) as well as the pigments and precious materials that will decorate the pages of the Gospels. And yet she connects those seemingly obscure references to deep and contemporary issues of faith and its place in our culture, making us see that the “grime / of letters traced upon the riven / calf-skin gleams dark as fresh ash on a shriven / penitent” (“Lampblack”).

Range’s poetic voice pulls medieval imagery and seemingly obscure literary references into an important poetic present, where “this good news is for everyone, / like language, like color, like air” (“Scriptorium”). It’s only the second of August – plenty of time left in the glorious summer to revel in her poems.