If my twitter feed is any indication, much of the United States watched Jesus Christ Superstar on NBC last night and loved every minute of it. I loved it as well, and I spent a lot time thinking about the medieval aspects of the production, a topic that would probably surprise many of the cast members.

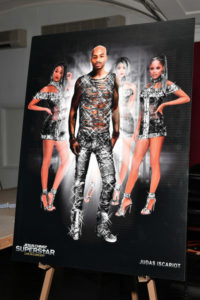

The set was brilliant – open scaffolding, a “deteriorating basilica” ceiling and back wall, an open fire pit (how’d they get a permit for THAT?), and an asymmetrical, multi-segmented stage that allowed the dancers and main cast members to get close to different parts of the audience. The costumes nodded to biblical-theatrical convention (John Legend’s deliberately timeless pants and shirt) as well as to the musical’s roots in the 1970s (Brandon Victor Dixon’s outfit for the last number) and to our contemporary moment.

But the medieval vibe came not from the set or the costumes but from the event. All evening, I felt like I was having an experience something like that of the audience of one of the medieval miracle plays. In late medieval England, communities gathered on Corpus Christi day (21 June) to perform what we now call Cycle Plays — a series of dramatic re-enactments of the narratives of biblical history. The City of York actually still produces its Cycle, although quadriennally rather than annually.

With a probable origin in smaller-scale re-enactments in the church building, by the late Middle Ages the English cycle plays had moved out of the church and into the community with elaborate portrayals of the Creation of the World, the story of Noah, the Last Judgment – and many, many highly focused episodes of the Life of Christ. These included the Last Supper, the trial before Herod, the raising of Lazarus, and of course the betrayal and the Crucifixion. Last night, we watched John Legend as Christ submit to the Crucifixion just as medieval English people watched one of their neighbors enact Christ’s death on the cross in the Cycle Play.

I watched the broadcast with a small group at a neighbor’s house, rather than in a large group of townspeople on the village green. But the live broadcast, an event now reserved almost entirely for sports competitions, provided that sense of larger community. Our band of neighbors knew that we were experiencing the performance in real time with thousands of other Americans and viewers all over the world. Because of the general decline in religous observance in the United States, many of those viewers were watching the performance as a cultural rather than religious experience. The Christiological narrative was the vehicle for the dancing and singing, rather than the opposite.

In the English Middle Ages, the Corpus Christi play was an annual event of civic pride and community celebration, and perhaps NBC will follow that medieval lead and present us every year with a version of Jesus Christ Superstar. If so, perhaps my future students will know the narrative of the life of Christ, whether or not they believe in it, seeing it as an important part of a shared, American cultural expression.