Last Friday, I visited the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library on the History of Women in America. What business, you might ask, did the Massachusetts Medievalist have at an institution dedicated to American history?

I’m at the tail end of a project I started five-plus years ago, currently titled Public Medievalists, Racism, and Suffrage (yes, I need a better title! suggestions welcome!). The Schlesinger visit was a crucial part of the “suffrage” focus, because I am investigating uses of medievalist imagery by the American suffrage movement and had hit something of a wall. The American suffrage activists were following the lead of their U.K. sisters, who used the language of crusade and Joan of Arc to describe their “quest” for voting rights.

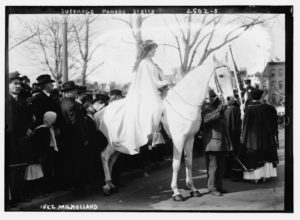

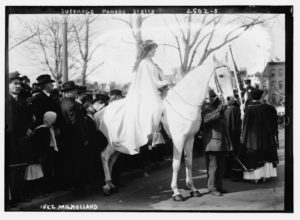

The most famous example of the medievalist impulse in American suffrage history is Inez Milholland’s performance as the “herald” of the Women’s Suffrage Parade in Washington D.C. on 3 March 1913.

With her crown, sweeping white cape, flowing hair, white horse, and riding gloves shaped like armored gauntlets, Milholland provided a medievalist illustration of the glamour of the suffrage movement. The cover of the parade’s program, expensively printed in color, exaggerated Millholland’s medievalist costume in its extravagant trappings for the horse, the billowing purple cape, and the “Votes for Women” flag on the trumpet.

I was having trouble, however, finding less-famous medievally-inspired suffragettes, and so turned to the experts at the Schlesinger for assistance. Ellen Shea, Head of Research Services at the Schlesinger, gave me an overview of some of their excellent finding aids and research guides. To be honest, I had looked around on their website quite a bit before making the appointment, had found the amount of information overwhelming, and had not found anything useful for my topic. Ellen did a great job making their vast resources seem much more manageable and focused.

With Ellen’s help, I found many medievalist-suffragist primary sources, most of which will end up in the book. Right now, I want to share two images (I’m figuring that it’s okay to post these images here, since I retrieved them from the open-access via.harvard.edu) that show that the medievalist impulse in American suffrage went further than Inez’s 1913 parade outfit.

The first shows two participants in the Boston suffrage parade of 2 May 1914; they were specifically dressed as Joan of Arc and Isabella of Spain (Ellen found that information for me too, in a contemporary Boston Globe article). Like Inez, these women ride astride, not side-saddle, and they seem to be having a good time. They were probably inspired by Inez, at least to some extent, although they have chosen to depict specific medieval women rather than invoking the Middle Ages more generally.

The medievalist imagery extended as well to the American collegiate suffrage movement, as the Stanford University chapter of the Collegiate Woman Equal Suffrage League used the image of a questing knight to advertise the club’s meeting in “Roble Hall Saturday 2pm Sharp.” The Stanford Knight-Lady’s horse wears a fabulous fleur-de-lis caparison; her accessories include a sword and the banner proclaiming the club’s name and featuring a crowned queen in a sunburst. Unfortunately, the Stanford suffragettes didn’t include date or year on their poster, and the Schlesinger notes it only as 1903-1926, so we have no idea if the poster could have been inspired by Inez’s 1913 performance.

All of these images draw on contemporary, popular conceptions of the European medieval world to proclaim American female strength and perseverance in the activist’s fight for full citizenship. That’s why the Massachusetts Medievalist was at the Schlesinger Library, and my trip there proves a point I make continually to my students: When in doubt, ask a librarian!