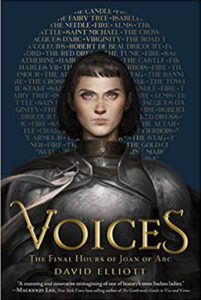

Between watching the crocuses bloom and the robins feast, the Massachusetts Medievalist this past weekend spent some time with my colleague David Elliott’s brilliant and disturbing new book, Voices: the final hours of Joan of Arc.

Ostensibly a YA verse-novel, Voices is genre-defying. It is indeed all poetry, but it’s not a novel (although it provides a narrative), it’s not a biography (although it relates the crucial events in the life of the historical woman we call Joan of Arc), and it’s not even really “YA” (whatever that amorphous term means). Elliott has made a space to experiment with a variety of voices as he explores the life of Joan of Arc, probably the most recognizable medieval woman in our contemporary pop culture.

For those who need a refresher: Joan was a teenage peasant girl who followed the instructions she heard in her head from Saints Catherine, Michael, and Margaret to wear men’s clothes and lead the French king to victories in battle during the conflict known as the Hundred Years War. She was captured by the English in 1430, tried as a heretic, and then burned at the stake in 1431.

Elliott has given voice to a number of the inanimate objects that figure in Joan’s narrative: we hear the thoughts of the armor she wore, the church altar she prayed before, the sword she used, even the crossbow that wounded her in battle when she was captured. As she stands bound to the stake of execution, Joan herself speaks her own narrative – while the fire grows around her, she tells and reflects on her own story. The fire itself speaks as well, the most frequent narrator after Joan.

Elliott’s accomplishment here – and that of the editor and type-designer who supported him – is remarkable on a number of levels. Other than Joan, the characters and voices speak using late medieval poetic forms like the triolet or the rondeau (helpfully listed in the author’s note at the end of the text), forms that Joan and her communities would have known. Some of these poems are also presented as shape-poems: the sword’s episode is presented on the page in the shape of a sword, for example. Joan herself speaks in what Elliott calls “a kind of toned-down spoken word,” with varied line lengths, internal rhymes, and startling, individualized imagery and diction. Direct quotations (in Modern English, not French!) from the Joan trial transcripts are scattered throughout the text. I can only imagine the consternation at the Houghton Mifflin marketing department: you want us to sell WHAT?

And yet it works. By the end, we know Joan, her thoughts, her dreams, her beliefs, and we dread the fire and the ending even as we know it is inevitable. While I’d recommend Voices to anyone, I especially want my colleagues in medieval studies to read it, to see the ways that contemporary authors continue to reshape the texts of the Middle Ages in exciting and provocative ways.

To whet that appetite, some lines spoken by Joan’s war horse (part of a rondel):

Many a knight had been cowed and outdone

by my spirit, left broken, unseated, unmade.

But she understood. Unbridled blood runs

molten and wild, unrestrained, unsurveyed.

And she was like me and so we were one.

And coda: my colleague Anthony Apesos has made a series of paintings loosely based on the Tarot deck, thematically appropriate in a week where I helped the sophomores struggle through T.S. Eliot’s “Waste Land.” See his unsettling and beautiful “deck” here as well as his kickstarter page, where he explains the “suits” in his deck and some of his thinking behind the images. Enjoy!